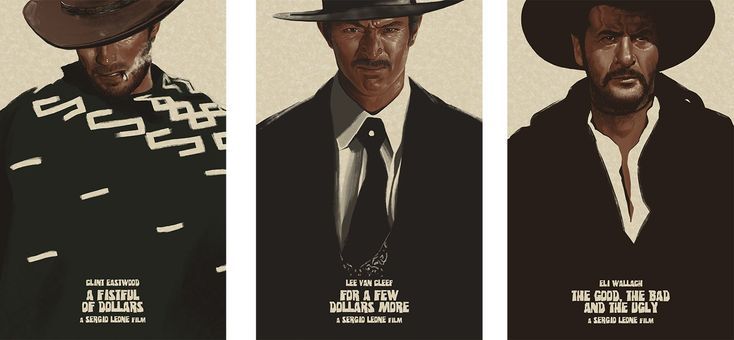

Alright, saddle up, pardner, because we’re about to mosey through Sergio Leone’s Dollars Trilogy—A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly—with a grin wider than Clint Eastwood squinting at a saloon full of bandits.

First up, A Fistful of Dollars—a movie so lean and mean it makes a rattlesnake look cuddly. Eastwood’s Man With No Name strolls into town like he’s auditioning for the role of “guy who invented brooding,” and within five minutes, he’s got two rival gangs tripping over their spurs to kill each other. The plot’s simpler than a one-horse town: Clint smirks, shoots, and somehow makes a poncho look like high fashion. The only downside? Every character’s so sweaty and dusty, you’ll want to shower just watching it. Five gold coins out of five for sheer swagger.

Next, For a Few Dollars More doubles down like a barfly ordering a second whiskey. Eastwood teams up with Lee Van Cleef, whose face looks like it was carved from a particularly grumpy oak tree, to hunt down a cackling psycho named El Indio. It’s got more twists than a sidewinder on a bender, and the tension’s so thick you could cut it with a Bowie knife. The music? Ennio Morricone’s score slaps harder than a duel at high noon (more on this later). Bonus: So many close-ups of sweaty eyebrows. Four and a half dollars for effort.

Finally, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly—the crown jewel of the trilogy, or as I call it, “Three Hours of Clint Eastwood Looking Like He Smells a Dead Rat.” This time, he’s joined by Van Cleef (the Bad) and Eli Wallach (the Ugly), who steals the show like a bandit running off with your last tortilla. It’s a treasure hunt with more double-crosses than a tic-tac-toe tournament, set against a Civil War backdrop grittier than sand in your boots. The final standoff? So tense I forgot to blink. Downside: by the end, you’ll be humming that “wah-wah-waaah” theme until your dog howls for mercy. A solid six shootin’ stars out of five.

In short, the Dollars Trilogy is a rootin’-tootin’ masterpiece of squints, shootouts, and style. It’s so good, even the horses deserve an Oscar. Just don’t ask where Clint keeps his spare bullets in that poncho—some mysteries are best left unsolved.

Meet the Villains

The movies also give us villains so dastardly they’d steal the gold fillings from their own grandma’s teeth, assuming they hadn’t already shot her for snoring too loud. These baddies aren’t just mean; they’re a laughable mix of over-the-top bravado, questionable life choices, and a knack for getting outsmarted by a squinting Clint Eastwood. These spaghetti Western scoundrels include,

A Fistful of Dollars – Ramón Rojo: The Overachieving Rifle Nut

Ramón Rojo (Gian Maria Volonté) is the kind of guy who’d RSVP “yes” to a massacre and bring his own ammo. This slick-haired psycho runs the Rojo family like a discount mob boss, wiping out a Mexican army for some gold because apparently, petty theft wasn’t evil enough. He’s obsessed with his rifle—probably sleeps with it under his pillow—and struts around like he’s auditioning for “Most Likely to Monologue Before Dying.” Spoiler: he loses a duel to the Man with No Name, who’s secretly wearing a steel plate under his poncho. Imagine Ramón’s face when his bullets bounce off like ping-pong balls—priceless! Maybe next time, buddy, aim for the head instead of flexing your sharpshooter ego.

For a Few Dollars More – El Indio: The Melodramatic Hipster

Then there’s El Indio (Volonté again, because apparently he’s the only guy in Italy who can sneer properly), a bandit with a musical watch and a vibe that screams “I peaked in drama school.” This guy’s got a tragic backstory—killed a girl, kept her boyfriend’s watch as a memento—and now he’s all brooding and cackling like a discount Joker. He leads his gang with the energy of a caffeinated poet, puffing on joints and giggling through shootouts. His big plan? Rob a bank! His bigger flaw? Underestimating Colonel Mortimer and the Man with No Name. El Indio’s last note? A sad little trill from that watch as he flops dead.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly – Angel Eyes and Tuco: The Ice King and the Yappy Chihuahua

In The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, we get a villain double feature. First up is Angel Eyes (Lee Van Cleef), the Bad, who’s so cold he’d ice his own coffee with his stare. This guy’s a hired gun chasing Confederate gold, and he’s got the charm of a rattlesnake with a tax bill. He tortures Tuco for info, kills without blinking, and looks like he’d sue you for stepping on his boots. His end? Shot in a three-way standoff because he didn’t realize Blondie’s the real brains here. Tough break, Angel Eyes—maybe stick to glaring contests next time.

Then there’s Tuco (Eli Wallach), the Ugly, who’s less a villain and more a walking disaster with a bandit badge. This greasy loudmouth bounces between betraying Blondie and begging for his life, all while yelling like a donkey stuck in a saloon door. He’s got a rap sheet longer than his unwashed beard—robbery, murder, impersonating a Mexican (badly)—but he’s so clumsy you almost root for him. Picture him dangling from a noose in the finale, whining as Blondie rides off with the gold. Tuco’s the guy who’d trip over his own spurs trying to rob a piggy bank.

These villains are a hoot because they’re so extra—Ramón’s rifle fetish, El Indio’s emo playlist, Angel Eyes’ icy one-liners, and Tuco’s nonstop tantrums. They strut into town thinking they’re the toughest hombres around, only to get outfoxed by a poncho-wearing drifter who barely talks. Leone serves them up with a side of Ennio Morricone’s twangy tunes, making them the perfect mix of menacing and ridiculous. In the end, they’re not just bad—they’re hilariously bad at being bad.

Music

Ennio Morricone’s music for the Dollars Trilogy is the sonic equivalent of a gunslinger’s glare—haunting, unforgettable, and dripping with swagger. From the eerie whistles and twanging guitars of A Fistful of Dollars to the mournful trumpets of For a Few Dollars More, and the iconic “wah-wah-waaah” of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, his scores don’t just accompany the films—they are the pulse of the Wild West (though shot in Spain). Morricone turns silence into tension and gunfire into melody, proving that a good soundtrack can outdraw even Clint Eastwood’s quickest trigger finger.

The Dollars Trilogy was shot in the sun-scorched wilds of Spain’s Almería region, a stand-in for the American West that’s so convincing you’d swear Clint Eastwood spat tobacco on a cactus. Sergio Leone traded Monument Valley for Tabernas Desert’s rugged hills and dusty plains, where the stark, bleached landscapes amplify the trilogy’s gritty showdowns. The crumbling villages and rocky outcrops, like those near Colmenar, became timeless backdrops for poncho-clad vengeance. It’s a place so desolate, even the scorpions look thirsty—perfect for a trio of films where every shadow hides a gun.

Cinematic Influences

These movies left an indelible mark on cinema, reshaping the Western genre and influencing countless filmmakers. Inspired by Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, Leone infused the trilogy with a gritty, morally ambiguous tone, departing from the clean-cut heroism of traditional American Westerns. Clint Eastwood’s iconic Man with No Name, a laconic antihero driven by self-interest, redefined the cowboy archetype. Ennio Morricone’s haunting scores, blending twangy guitars and eerie whistles, became as legendary as the films themselves, influencing everything from Quentin Tarantino’s stylized violence to modern video game soundtracks like Red Dead Redemption. Leone’s use of wide-angle cinematography and tense, drawn-out standoffs birthed the “Spaghetti Western” subgenre, impacting directors like Sam Peckinpah and even extending into sci-fi and action films. The trilogy’s raw cynicism and visual flair continue to echo across pop culture, proving that a fistful of dollars can buy a legacy.

These movies are also a masterclass in cinematography, with Leone and his cinematographer, Tonino Delli Colli, revolutionizing the visual grammar of the Western genre. Leone’s approach leaned heavily on extreme contrasts, both in composition and lighting, to amplify the gritty, sun-scorched desolation of his Spaghetti Western world. His use of wide-angle lenses, particularly in expansive desert vistas, stretched the frame to mythic proportions, making characters appear both dwarfed by their environment and larger-than-life. The trilogy’s iconic close-ups—tight shots of weathered faces, sweat-beaded brows, and darting eyes—built unbearable tension, especially during standoffs, where rapid cuts between perspectives heightened the drama.

Leone’s framing was deliberate and painterly, often juxtaposing vast emptiness with claustrophobic detail. In The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, the Civil War backdrop is captured in sweeping long shots, while the final three-way duel uses circular pans and precise blocking to turn a cemetery into a gladiatorial arena. His mastery of depth of field kept foreground and background in sharp focus, a technique that made every dust mote and distant rider integral to the story. The trilogy’s warm, arid color palette—burnt oranges, dusty yellows, and deep shadows—evoked a harsh, unforgiving frontier, contrasting sharply with the lush greens of classic Hollywood Westerns. This visual style not only defined the Spaghetti Western aesthetic but also influenced filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez, cementing Leone’s cinematographic legacy as a cornerstone of modern cinema.

Sergio Leone’s spaghetti Westerns are so iconic, they’re practically the cinematic equivalent of a tumbleweed rolling through your grandma’s living room while she’s trying to knit.

Leave a comment