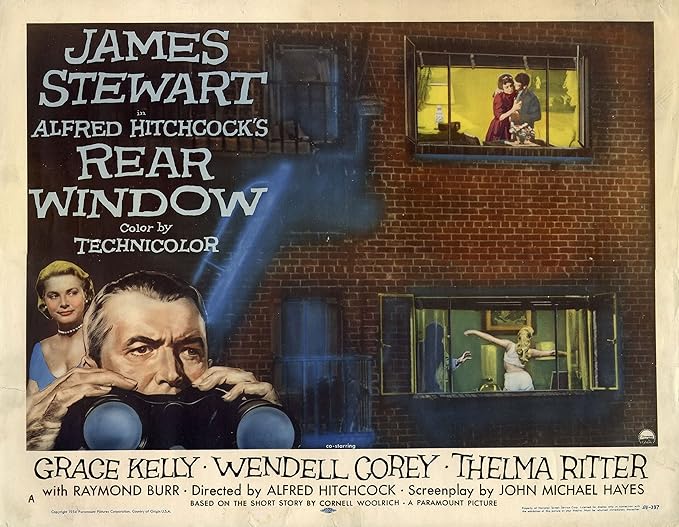

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Starring: James Stewart, Grace Kelly, Raymond Burr, Thelma Ritter

Rear Window is my kind of thriller. There are no jump scares. There are no contrivances. The movie meticulously presents a tapestry of events that shapes into a thriller, like a slack rope slowly pulled taut.

We are introduced to L B Jefferies, a curmudgeonly James Stewart, a self-professed independent man of action temporarily confined to a wheelchair for six weeks. His frustration is palpable. One moment, he is in the middle of a race car circuit, taking daredevil photos (which is why he was in the cast in the first place), and the next, he is invalid, having to rely on women to even reach his equipment.

But it is not just Jefferies who is handicapped. We, the audience, are chained along with him in his helplessness. Alfred Hitchcock does not show us anything that Jefferies cannot see. Jefferies’ point of view is our point of view. His inability to intervene, to take or evade action, is passed onto the viewer. In this way, Hitchcock fuses the protagonist’s perspective with that of us viewers.

There is an even more fundamental behavior that binds Jefferies to viewers. Jefferies is a compulsive voyeur. One can safely assume that even when his legs were intact, he primarily viewed the world through his camera. With nothing else to do during his recovery, he reaches for his binoculars and trains them onto the red-brick facade that faces his rear window. There, he watches, without guilt, glimpses of lives presented to him through the windows of his many neighbors.

And what a menagerie he gets to pick from!

There is young “Miss Torso”, a vivacious dancer who entertains young men who hope to make her their sweetheart. Then there is “Miss Lonelyhearts”, whose solo life seems to drive her mad with grief and sorrow. “Mr. Music Composer” doesn’t seem to get just the right notes and texture for his music. A few more interesting characters occupy the buildings facing the rear window. Each is unique but almost two-dimensional, offering Jefferies (and us) viewing entertainment.

Along with Jefferies, we also watch their lives with curiosity. We are all voyeurs in some way. Rear Window plays on our rubbernecking tendencies to a remarkable degree, intertwining movie-making and movie-watching into a joint exercise of guilty pleasure.

“We’ve become a race of Peeping Toms. What people ought to do is get outside their own house and look in for a change.”

When Stella admonishes Jefferies with the above line, we feel chastened. But when Jefferies impatiently trades in his binoculars for his zoom lens – because he can’t see clearly into apartment windows – we lean forward again squinting. Our complicity is complete. We are ensnared. The trap is laid.

The first half of Rear Window also introduces us to Lisa Fremont (Grace Kelley cannot be more fashionable and resplendent), a goddess and diva who is an absolute catch for an itinerant photographer. Lisa Fremont practically throws herself at Jefferies, who stiffly and unconvincingly rejects her advances. Jefferies’ excuses to Stella about why he doesn’t reciprocate Lisa’s feelings reveal how much Jefferies is unsure of himself. The wheelchair situation must not have helped surely.

“She’s too perfect, she’s too talented, she’s too beautiful, she’s too sophisticated, she’s too everything but what I want.”

Once the stage has been set, Hitchcock moves on to the piece de resistance. The murder (if any) is never shown. Jeffries hears a scream. We are shown some events that could or cannot be contrived to indicate foul play. Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr brings the right amount of brooding, hulking menace to the character), who seems to have had a less-than-stellar marriage, seems to have sent his bed-loving wife to her home. But why is he washing saws and knives? Why isn’t he curious when a neighbor’s dog dies in the backyard, and everyone is leaning over their balustrades? Isn’t it natural to show some curiosity over such an incident?

By now, everyone, including the audience and the Jefferies ensemble crew, Stella and Lisa, is convinced something is amiss.

This is why I love this movie. Hitchcock never employs jump scares. He does not play with lenses to pull cinematic shortcuts and multiple perspectives. A hallmark of great filmmakers is that they hold the camera steady, giving viewers and characters the same shared perspective and building tension with the plot and events. The world does not have to whirl around. Jump cuts are unnecessary to build momentum. There is no need for screeching musical crescendos.

Those are surprises, not suspense.

Suspense is when three ordinary people stare out of the rear window for a long time in silence, watching a salesman wash saws and knives, and one of them says

“Come on, that’s what were all thinkin’. He killed her in there, now he has to clean up those stains before he leaves.”

Leave a comment