The Jacaranda tree around the corner of the next block fizzed furiously with grape soda petals exploding in a million tiny floral bubbles. It is my favorite tree, and when it decides to bloom, I cannot walk past it without a stupid grin on my face. One day, it is an unobtrusive tree, a lone eco-warrior amidst fast-depleting greenery in a lane sold out by greedy realtors. The next day, it bristles with purple flowers, defiant and gleeful, daring anyone to look past its violent blooms.

I love the tree so much that I have planted a Jacaranda in front of my house. In one year, the sapling has managed to twist and turn its way to sunlight from under the canopies of the taller mango and Gulmohar trees that flank it on either side.

I hope all these trees fare well, what with vulture-like BESCOM tree pruners (murderers, more like) and overenthusiastic and unexplainably concrete-loving Home-Owners-Association functionaries hovering over any healthy, leafy tree that grows to a decent height.

Anyway, one hot afternoon, I found myself standing in the shade, admiring the Jacaranda tree dreamily. How its trunk was twisted and knotted, and how its boughs ended in creamy clumps of purple blooms. It looked like a melty blackberry cone from a 90s Indian advertisement, the golden era of Indian advertising.

I had just started noticing birds and looking them up at that time. At the very top of the tree, I could see a small black bird with an outlandishly curved beak.

I noticed the tiny bird because of the racket it was making. Because I had to squint into the sun, I couldn’t see anything but its silhouetted contours. I had recently read about Loten’s Sunbird, and I was starting to bounce slightly on my toes with excitement as soon as I discerned the ridiculously long curved beak.

Could it be? Could it be?

That evening, I looked up the bird online and figured out that the best way for a non-specialist to identify the bird was, indeed, with the bird’s beak. Armed with all this information, I walked towards the Jacaranda tree again – the same time the next day.

Quite honestly, I wasn’t even sure that’s how birds work. Are they creatures of habit? Do they frequent the same trees at the same time of day? Either way, I reasoned, the tree was in full bloom, and no other motive was needed.

The bird was there.

A plump black raisin on top of the tree.

The Loten’s sunbird.

From afar, what looked and acted like Susuwatari, Miyazaki’s naughty frizzly soot balls, up close shimmers and shines with iridescence—metallic green armor-plated head, glittering purple chainmail of a breast, and a maroon band across the lower chest (giving it another name—The Maroon Breasted Sunbird). Like how the Jacaranda transforms from frump to fab overnight, with just a light pirouette, the Loten’s Sunbird catches the sun, morphing from pure black to celestial shimmers.

The female is a lot less of a dandy but no less tastefully outfitted. The citrus yellow underpants with a brown shawl thrown over her shoulders slightly ground them as a pair. There is atleast one level-headed dresser in the family.

A characteristically long, downward-curving beak for both completes the family semblance. A device designed to reach deep into flowers that other species cannot reach. As if the beak was not long enough to probe deep into the hearts of flowers, these birds have an even longer tongue that uncoils and shoots out from the beak to lap up nectar from spots unreachable by lesser-evolved competitors. This is one of the reasons the Purple Sunbird and the Loten’s Sunbird overlap in their territory without competing for resources.

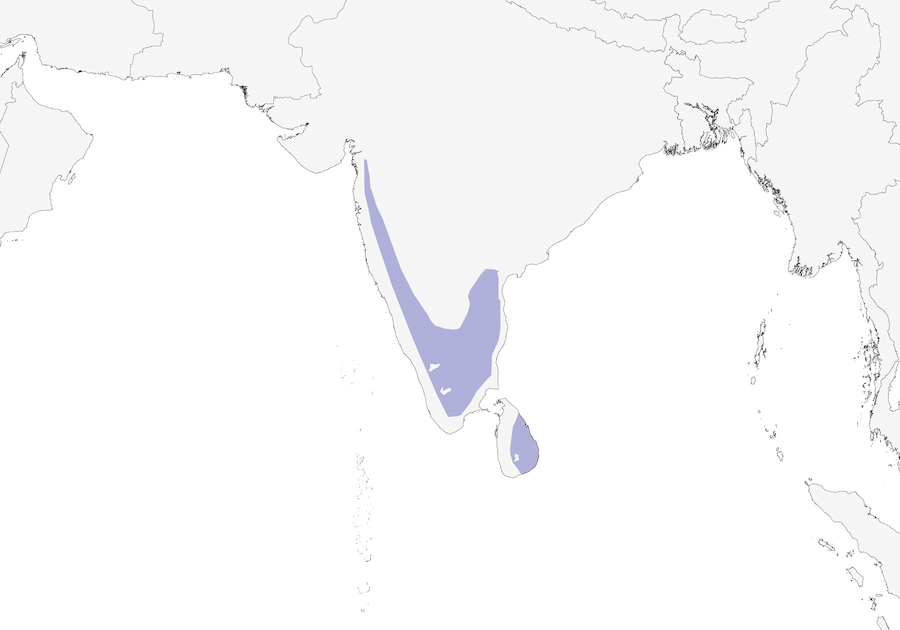

These birds are endemic to Peninsular India along the ghats and eastern Sri Lanka. Joan Gideon Loten, a Dutch Governor of Sri Lanka (1752-1757), conveniently “discovered” the bird (Cinnyris lotenius) and attained perennial fame among avian enthusiasts. Cheap move, if you ask me.

I’d have liked it if he was known as “The Sunbird Governor.”

Now that I recognized these tiny sunbirds, they started showing up more often. I even imagined seeing them on my drives to different towns in Tamil Nadu. Were these the ones flitting around sitting on telephone poles and electric wires? I felt lucky to get to spot these endemic species on demand.

Coincidentally, after that week, I started seeing the Loten’s Sunbird much more frequently. Every day, a male bird perches right outside my study on the highest branch of the pomegranate tree and makes it his business to disturb everyone with his chirps. Cheep-cheep-cheep, it goes angrily until no one can get anything done. I took my binoculars and studied it closely before it flew away. After some time, it returned and started announcing its presence with more incessant chirping.

I grabbed my binoculars again. A little less urgently this time.

By the third day, when Mira burst in with an excited “There is a Loten’s sunbird sitting right out appa!” I didn’t even lift my head when muttering wearily, “I know.”

Later, we found that the bird, along with his missus, had built a shabby nest above the jacaranda on the Bilpatre (Aegle marmelos) tree on our porch. The whole cymbal-crashing charade was all smoke and mirrors to distract any predators from noticing the other silent parent as it entered or exited the nest.

I had to give it to the male.

My ringing ears can attest to a job only too well done.

At night both the Sunbird and I sleep easy, knowing there is a drongo guard.

Leave a comment